Ce texte de Armin Hofmann est paru dans la revue bimensuelle Graphis (numéro 146, volume 25), 1969/1970. Ce numéro était entièrement dédié à la présentation de deux écoles: le Royal College of Art de Londres, et la Allgemeine Gewerbeschule Basel. Hofmann y présente ses réflexions sur la première année d’enseignement dans le cours de perfectionnement (International Advanced Program for Graphic Design), initié en 1968.

Ecole des arts décoratifs de Bâle: le cours de perfectionnement de création graphique

Ce n’est pas l’un des moindres problèmes de notre âge technique que la façon abusive dont nous nous servons de machines et d’automates pour reproduire en série des formes initialement crées en fonction de cas particuliers.

De ce point de vue, l’enseignement de design au sens moderne du terme n’en est qu’à ses débuts. Nos écoles d’art appliqué en sont restées, pour l’essentiel, aux principes (valant pour la confection d’ouvrages uniques) qui régissaient autrefois l’artisanat d’art. Les quelques entreprises tentées, en différents lieux, avec des succès divers, pour remédier à cet état de choses, sont demeurées des expériences isolées. Aucun modèle probant ne s’est encore dégagé.

La question reste posée de savoir quelle formation il faut donner à des hommes dont on attend qu’ils pensent et agissent, intrinsèquement, en créateurs, sans préoccupation du résultat pratique, sans contrainte dans le choix des moyens, sans souci de la mode. Moins encore s’est-on réellement interrogé sur la formation que doivent recevoir des hommes appelés à viser, par delà l’individuel et le particulier, des valeurs élargies aux dimensions du groupe, de la série, du système. De même ignore-t-on encore comment l’on éduque des intelligences aptes à faire œuvre conceptuelle – par exemple, à forger des concepts afférents aux notions de permutabilité et de complémentarité.

Surtout, on tient fort peu compte encore, dans l’enseignement dispensé aux futurs créateurs de formes, des responsabilités grandissantes qui leur incomberont dans l’exercice de leur profession. L’enseignement professionnel n’a pas encore abordé le problème des grands complexes où s’insère de nos jours l’activité pratique de tout créateur. Relier le particulier à la totalité, le singulier au général, la responsabilité mineure à la responsabilité majeure, telle est présentement l’une des tâches sans doute les plus importantes qui se posent à l’école de demain.

Par l’institution de ses cours de perfectionnement annuels de création graphique, l’Ecole d’art appliqué de Bâle cherche à cerner et sonder certains de ces problèmes mieux qu’elle n’a pu le faire jusqu’à présent dans le cadre de son enseignement ordinaire. En limitant son propos à l’étude d’un thème unique, elle souhaite être à même d’éclairer aussi complètement que possible la multiplicité des éléments dont se compose, de nos jours, l’esthétique du milieu (« Umweltgestaltung »). N’étant ni pressés par le temps, ni tenus d’aboutir à des résultats déterminés, nous avons l’espoir de dégager ainsi certains linéaments de la structure générale de notre future école de design.

«Signes»: quelques indications sur le contenu du premier cours annuel

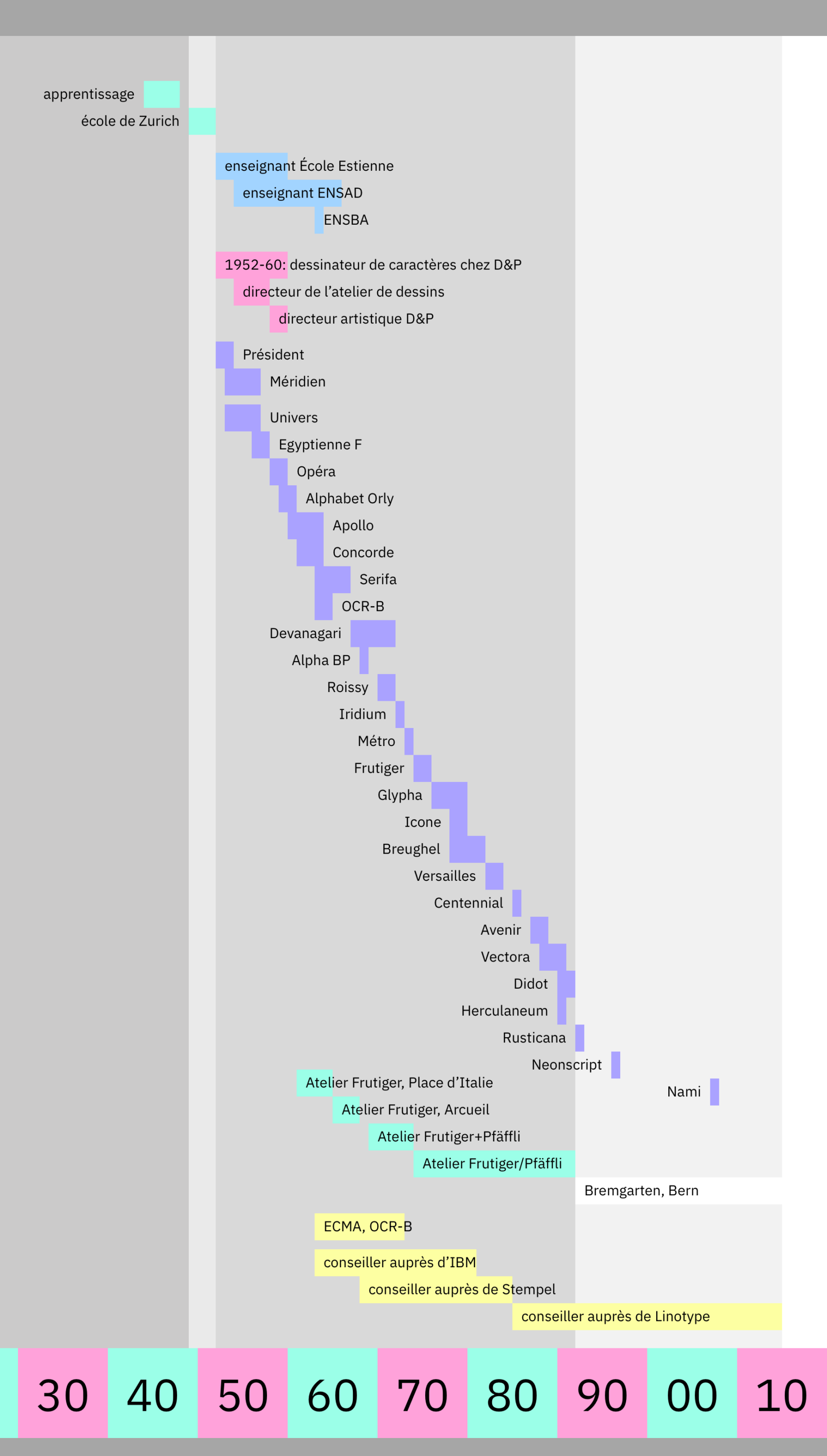

Le thème étudié la première année, sous le titre de «Signes», comportait un ensemble intégré de neuf cours pratiques.

- Trois d’entre eux (Signaux de sécurité, Variations, Typographie appliquée) avaient trait à la création graphique appliquée à l’esthétique du milieu (applied environmental design).

- Quatre autres (Processus du design, de la réalité au signe par l’abstraction, Architecture des signes d’écriture, Signes spatiaux) relevaient de l’étude fondamentale du design.

- Deux autres, enfin (Création libre, Cinéma), étaient réservés au travail expérimental.

- D’autre part, deux cours théoriques (Histoire de l’art appliqué, Collection-Classement-Documentation) visaient à élargir l’horizon des participants, et un séminaire d’une semaine (placé sous la direction de M. Colin Forbes, de l’Agence de publicité Crosby/Fletcher/Forbes de Londres) a été consacré à l’examen des notions fondamentales de l’économie de marché.

Les cours proprement dits étaient complétés, le soir, par des conférences au nombre desquelles il convient plus particulièrement de citer celles de M. Aaron Marcus, de l’Université de Princeton (Etats-Unis), sur le design d’ordinateurs, et de M. Adrien Frutiger (Paris) sur l’écriture pour ordinateurs.

L’élaboration du thème choisi présupposait une étroite coordination des diverses disciplines et une collaboration particulièrement harmonieuse entre les enseignants. Le plan d’études lui-même était conçu de façon à permettre, en tous sens, de multiples combinaisons et intercommunications.

Dans la suite de l’article, Hofmann détaille les différents cours:

- Processus de création, donné par Armin Hofmann.

- Variations, par Armin Hofmann.

- Signaux et panneaux de sécurité, par Max Schmid.

- Abstraction: la réduction au signe, par Kurt Hauert.

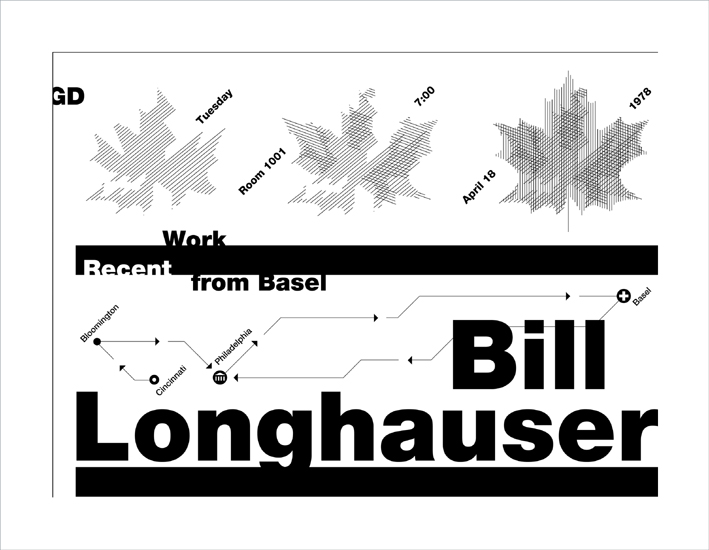

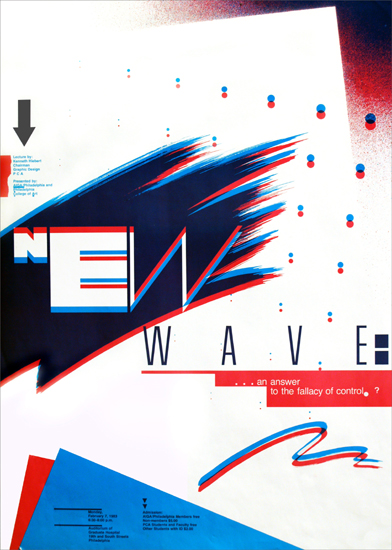

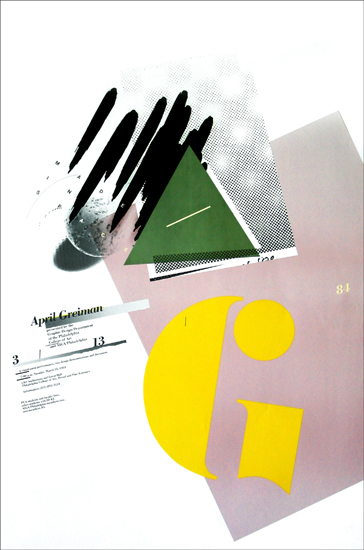

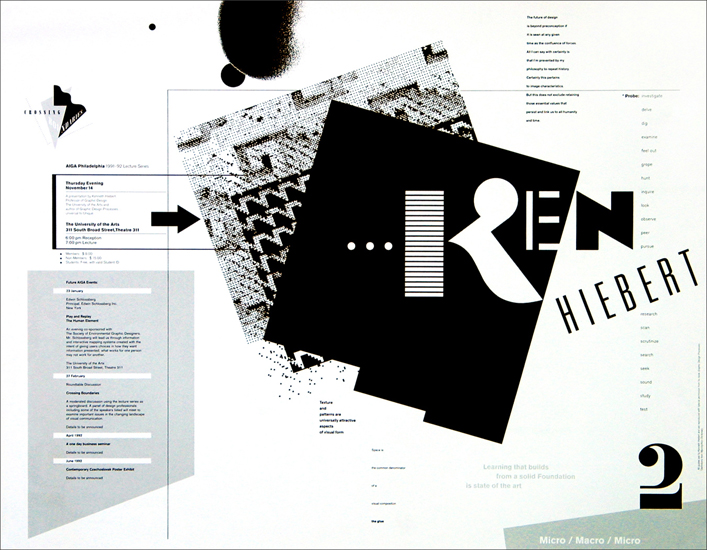

- Image typographique, par Wolfgang Weingart.

- Caractères (Schrift-Zeichen), par André Gürtler.

- Graphismes au cinéma et à la télévision, par Peter von Arx.

- Structuration de l’espace (Raumgestaltung), par Maria Vieira.

- Signe et Couleur, par Franz Fédier.

- Signes spatiaux (Räumliche Zeichen), par Johannes Burla.