Quelques notes sur la jeunesse et la formation d’Adrian Frutiger, selon le livre « Ein Leben für die Schrift », 2003, Schlaefli & Maurer AG, Interlaken.

Apprentissage à Interlaken : 1944–1948

À l’adolescence, Frutiger montre un grand intérêt pour le dessin. Ernst Eberhard, enseignant, le recommande à un ami imprimeur, ce qui permet à Frutiger d’y faire un apprentissage, dans un atelier d’imprimerie au plomb, l’imprimerie Schlaefli, entre 1944-1948 (de 16 a 20 ans). Dans les années de guerre, une grande quantité de tâches d’exécution est confiée aux apprentis, qui doivent maîtriser toute la chaîne de l’impression. Son patron lui permet l’inscription à un cours du soir en gravure sur bois.

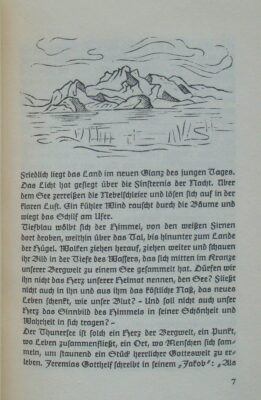

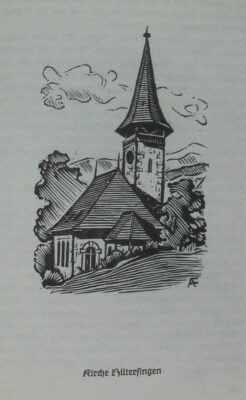

Dans son temps libre, Frutiger édite un petit livret « Die Kirchen am Thunersee »: un catalogue des anciennes églises autour du lac de Thoune. Il réalise les illustrations (gravures sur bois), rédige les textes et effectue la mise en page, dans une esthétique traditionnelle. Ce livret de 46 pages est édité en 1948 à 1000 exemplaires, pour honorer la fin d’apprentissage de Frutiger.

Etudes à Zurich : 1949–1951

Son but professionnel est de devenir artiste peintre ou typographe. Pour rassembler l’argent nécessaire aux études, Frutiger est apprenti pendant une année (en 1948) comme compositeur typographe dans une imprimerie à Zurich (Gebr. Fretz AG). À la Kunstgewerbeschule Zurich, il s’inscrit dans la formation de concepteur de caractères (Schriftgestalter), de 1949 à 1951. Il est le troisième élève à suivre cette formation spécialisée, après Hans Eduard Meier (de 1943 à 1945) et Max Kämpf. L’enseignement comporte deux branches principales: la calligraphie (« Schriftschreiben ») auprès d’Alfred Willimann (quatre demi-journées), et le dessin de caractères (« Schriftzeichnen ») après de Walter Käch (une demi-journée). Les autres cours obligatoires comprennent « Dessin d’objet » et « Perspective. »

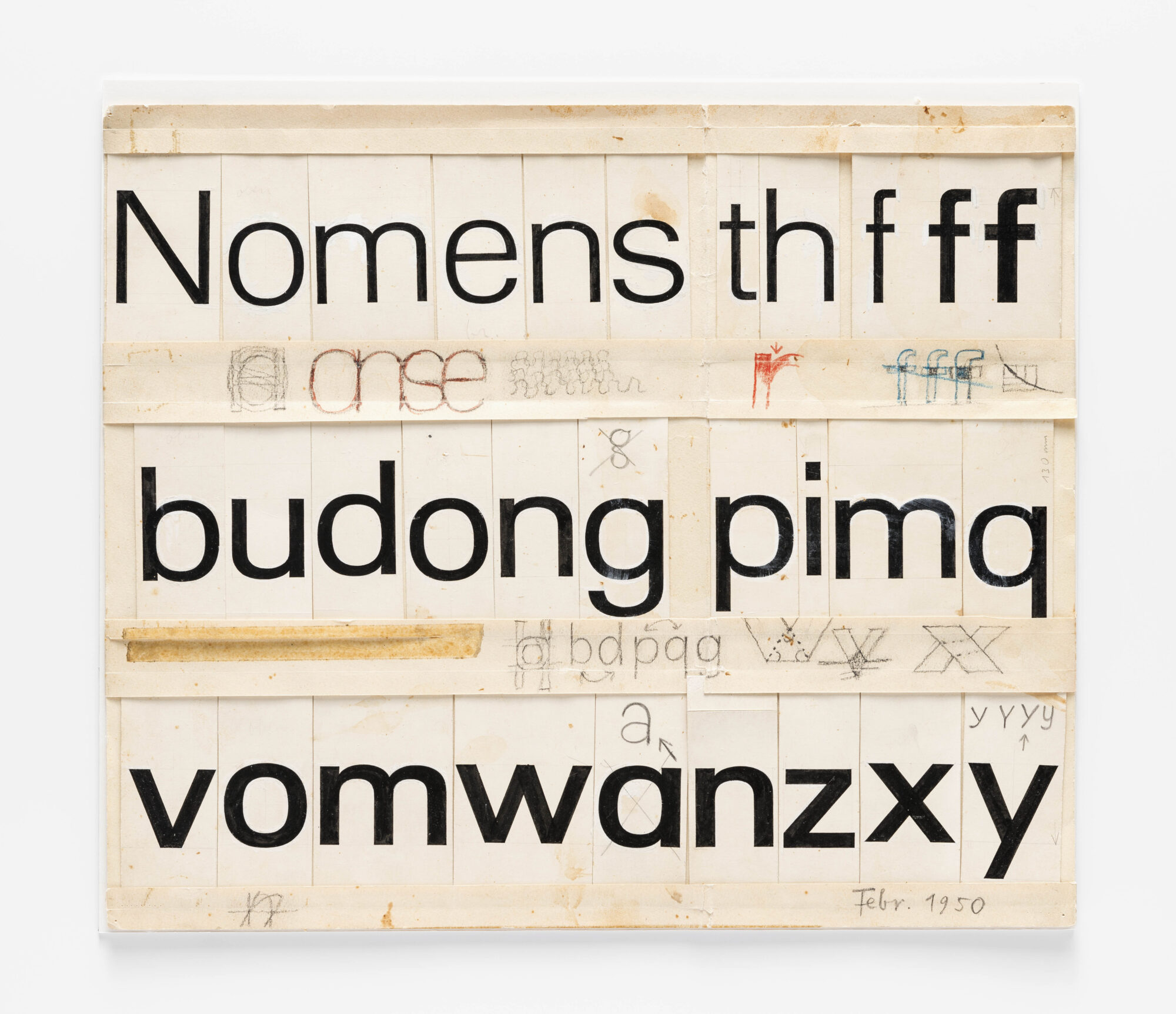

Walter Käch est un graphiste indépendant, formé par Ernst Keller, qui porte un intérêt particulier à l’étude des capitales romaines. Il visite des sites archéologiques en Italie pour produire des centaines de relevés d’inscriptions romaines. Il étudie minutieusement les proportions, l’épaisseur des traits, les courbes. C’est dans son cours que Frutiger a la vision d’une famille de grotesques, et développe les premières esquisses de ce qui deviendra Univers. Une esquisse datée de février 1951 est montrée dans le livre « Ein Leben für die Schrift » (p.23). On la trouve aussi sur le site eGuide du musée de design de Zurich.

Dans le cours de Willimann, Frutiger apprend l’évolution des écritures. Willimann enseigne comment la position de la plume influence le trait, décrit l’importance des espaces intérieurs et extérieurs, le rythme de l’écriture.

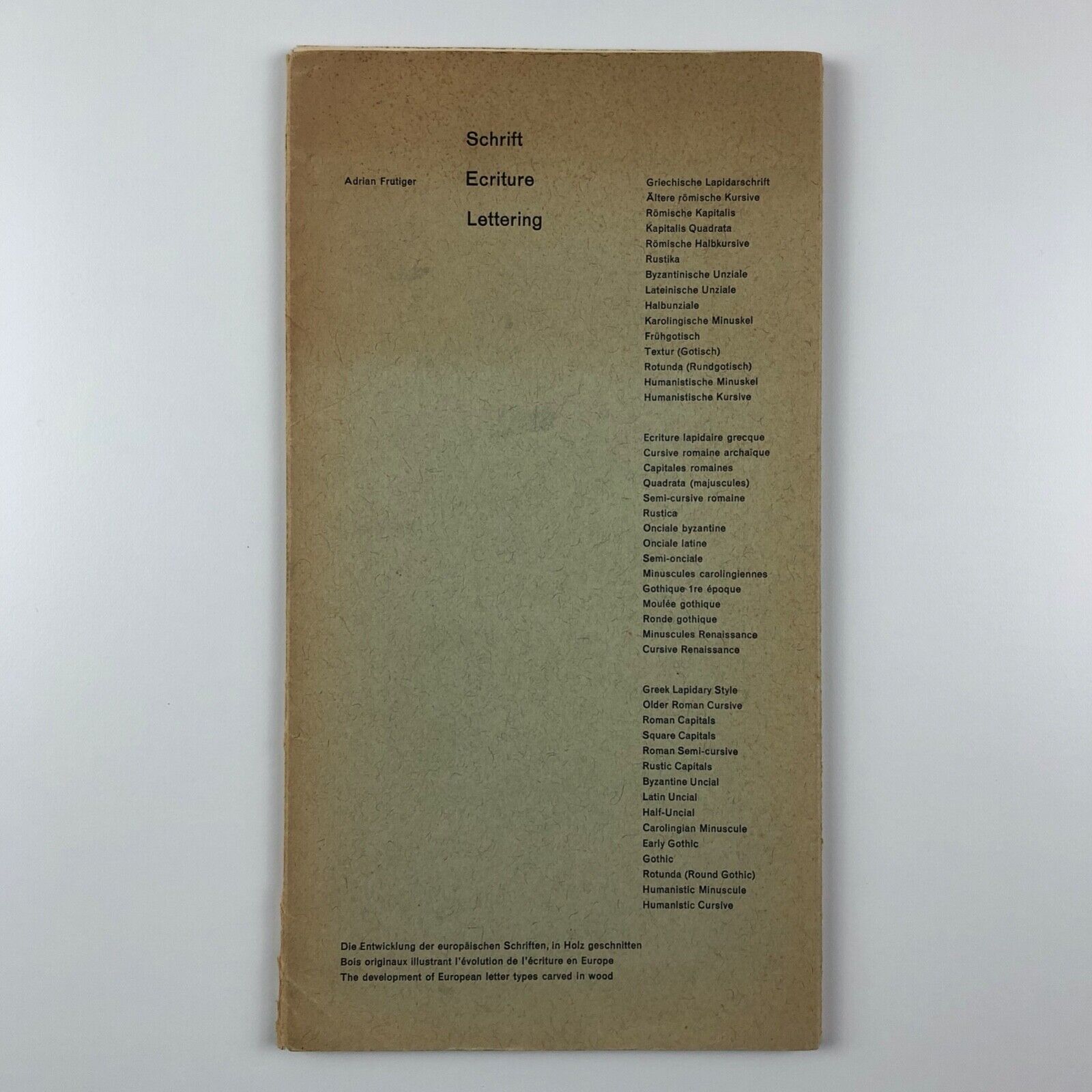

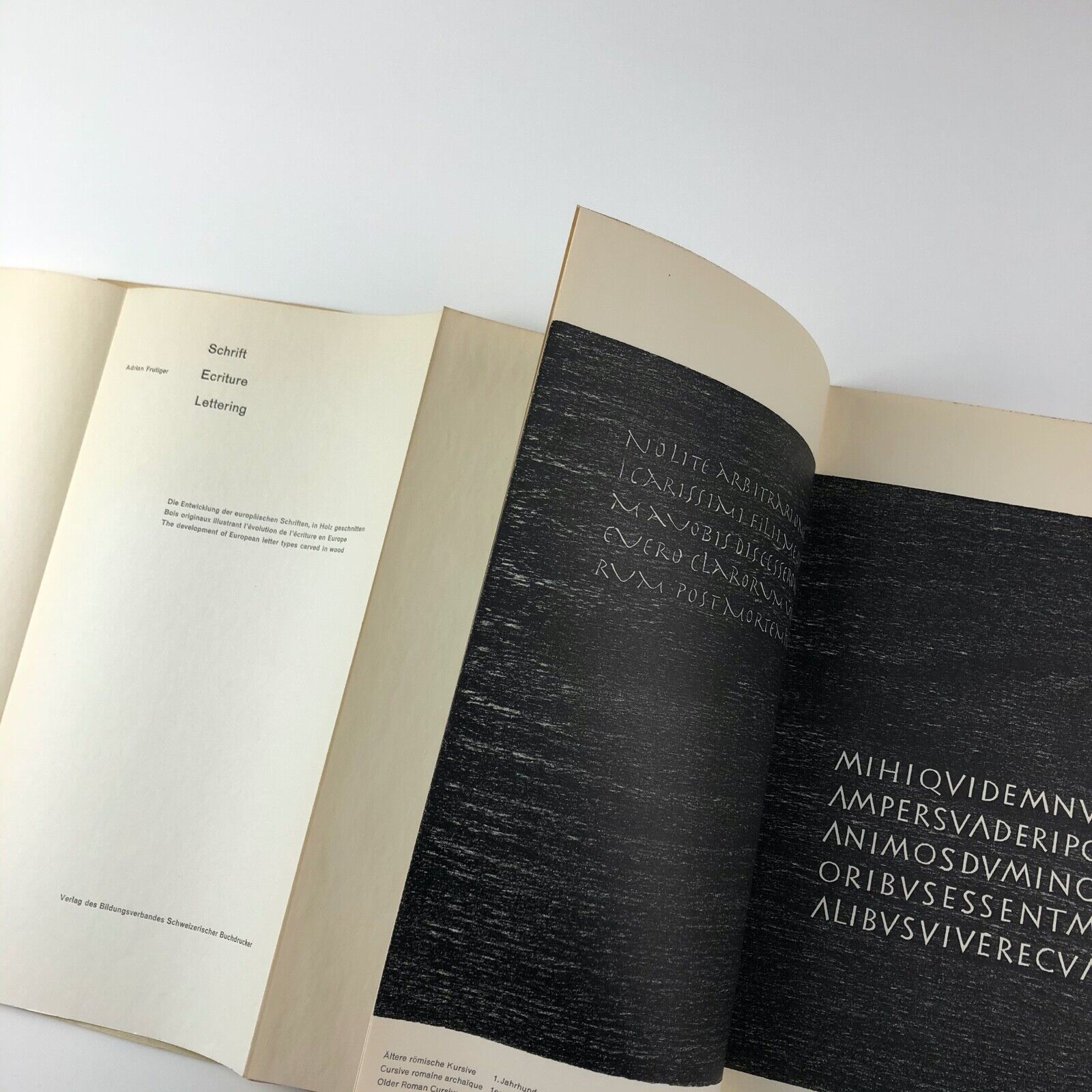

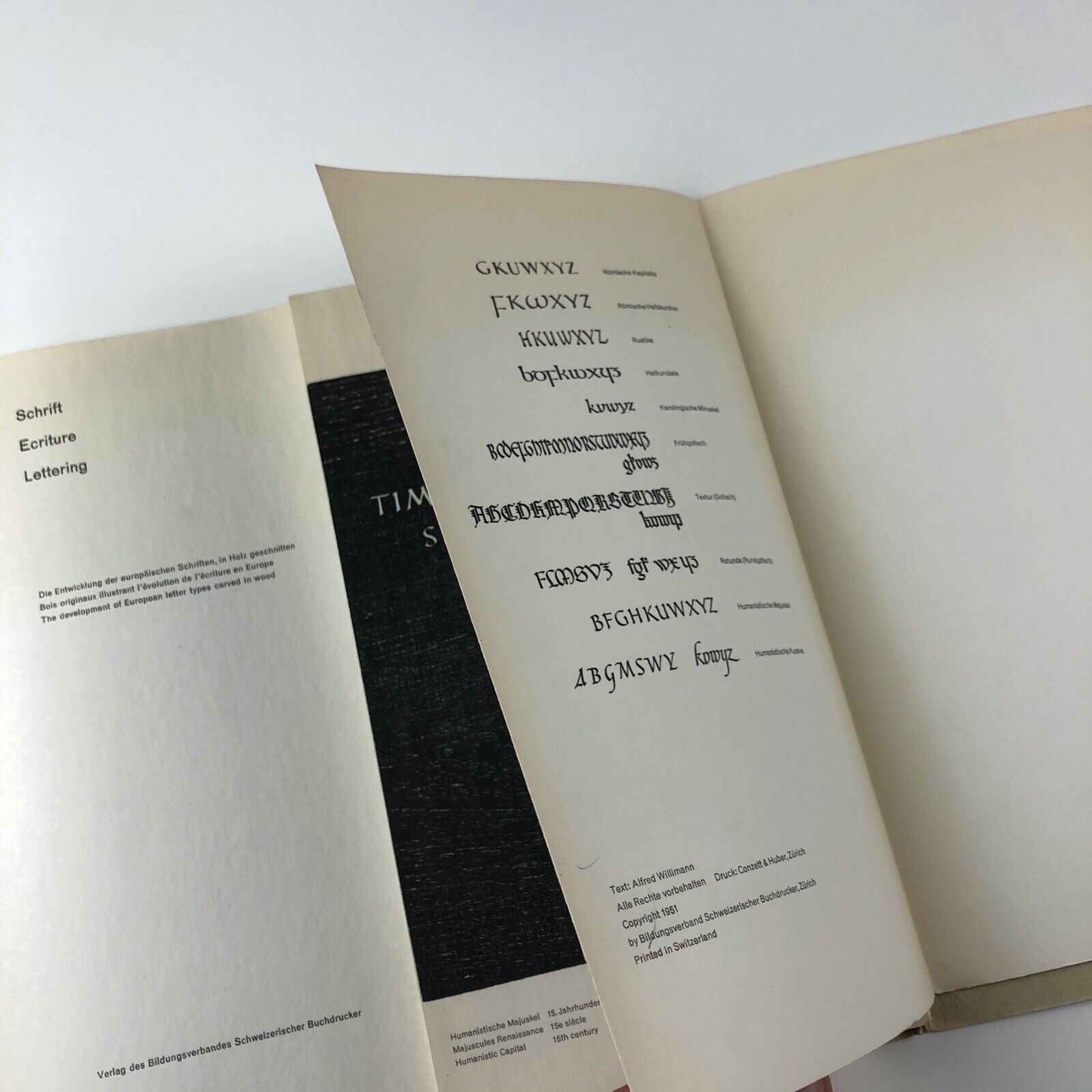

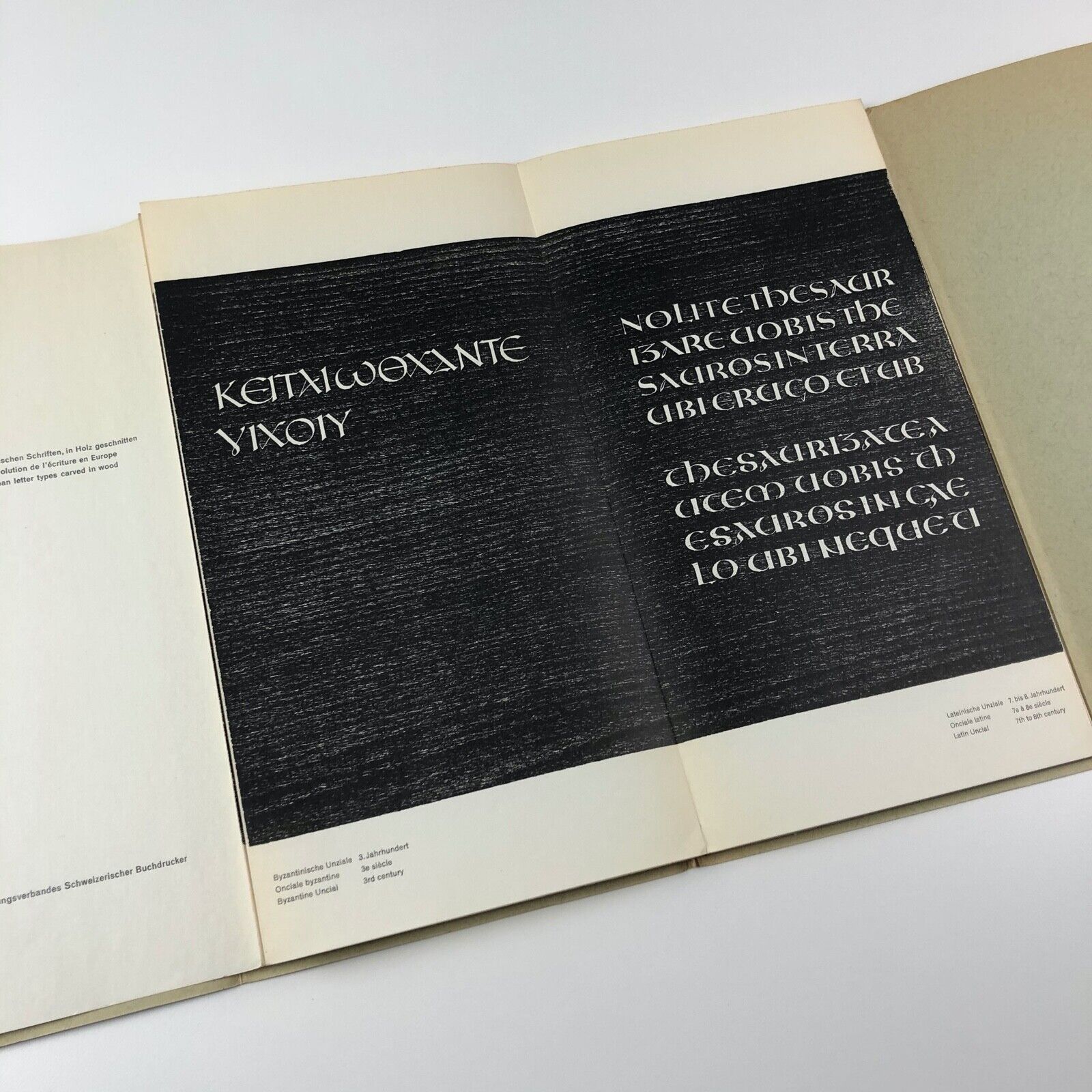

En 1951, Frutiger, âgé de 23 ans, réalise son travail de diplôme : « le développement de l’écriture occidentale, depuis le grec jusqu’à la minuscule humaniste ». Ne parvenant pas à produire des feuilles qui ne soient pas tâchées par ses doigts et exemptes de fautes d’orthographe, il décide de produire des planches imprimées. Il calligraphie l’écriture sur papier, puis la grave dans des planches de bois, pour aboutir à neuf plaques impeccables. Ce travail est édité en 1951 sous forme de leporello sous le titre « Schrift. Ecriture. Lettering. Bois originaux illustrant l’évolution de l’écriture en Europe », accompagné d’un texte d’Alfred Willimann.

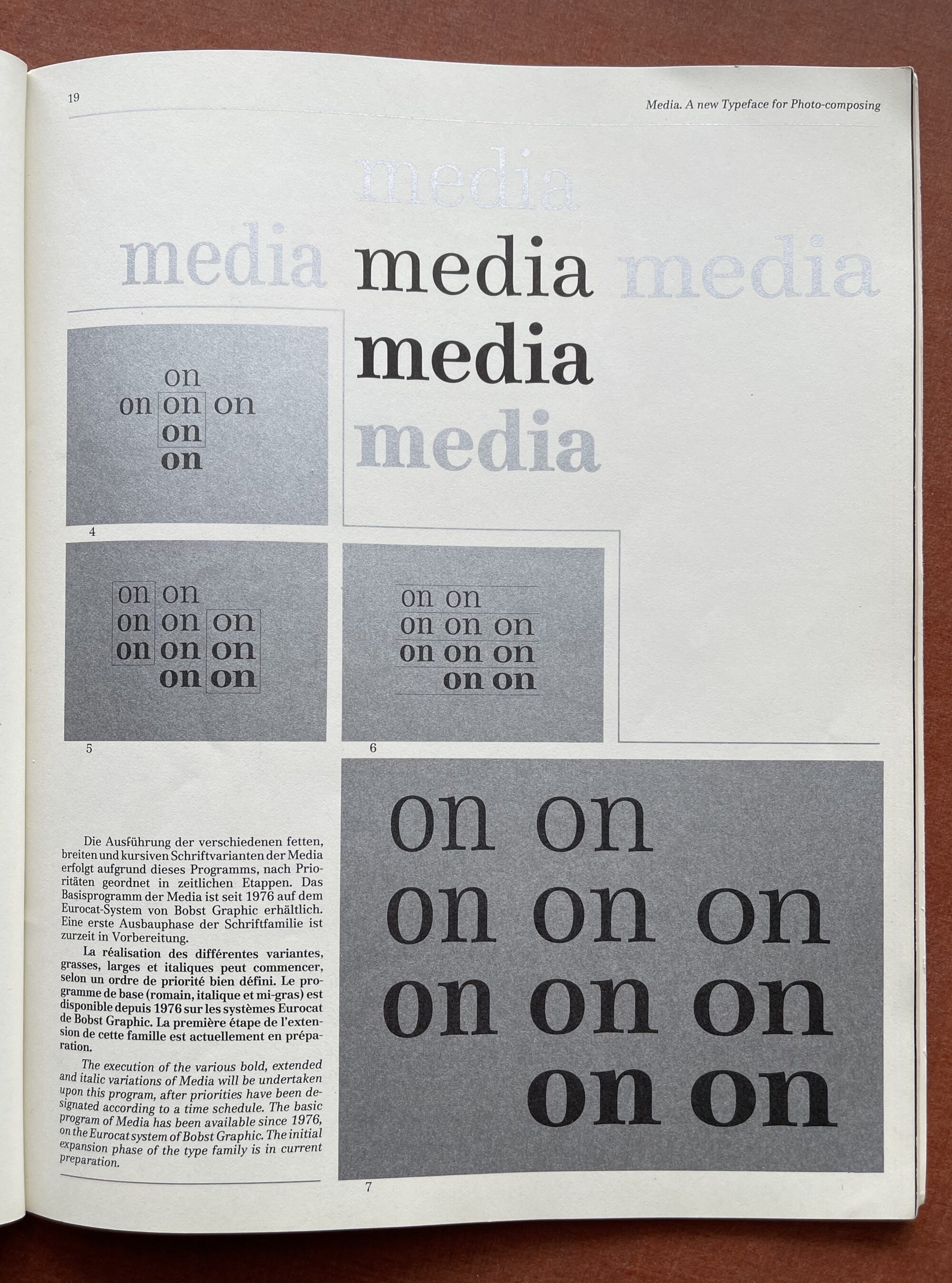

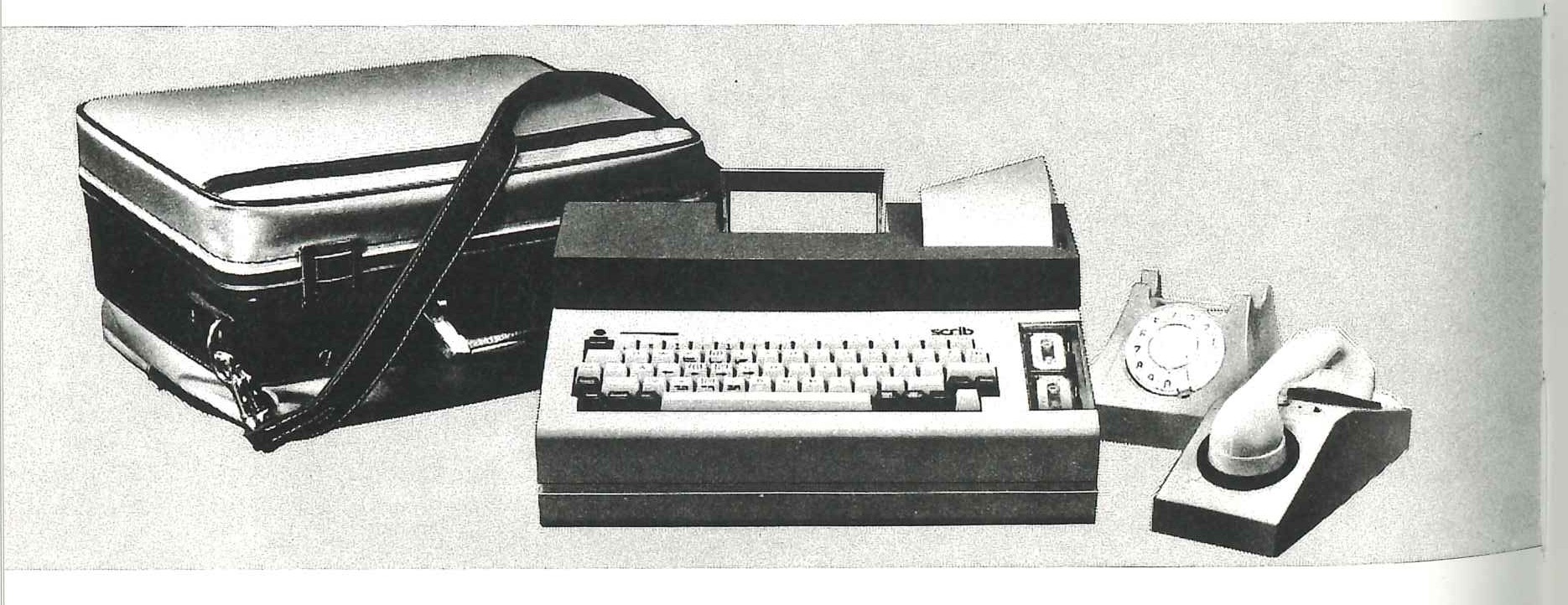

Frutiger envoie une copie de son travail de diplôme à toutes les fonderies d’Allemagne et de France, dont la fonderie Deberny & Peignot. Charles Peignot l’invite à venir travailler dans son entreprise pour une année. Charles Peignot a acquis la licence pour la construction du Lumitype pour l’Europe, et prévoit de produire des caractères pour ce système. Frutiger déménage à Paris en 1952. Frutiger est alors âgé de 24 ans.